To the north of the city of Djanet, the desert scenery is occupied by the spectacular rock face of the Tassili N‘Ajjer, a sandstone plateau that runs parallel to the dune belt of the Erg Admer, heading south-east to the Libyan border. The mountain of the Kel Ajjer, the Tuareg tribe that inhabits the region, hides in its inaccessible meanders one of the most incredible treasures that the Sahara desert has ever yielded.

A cultural park, UNESCO heritage site and biosphere reserve, the Tassili, which is about 500 km long, looks like a compact sheer cliff, which can only be crossed on foot or on donkeyback, through a few sporadic natural passages that climb and creep up its sides. On reaching the top of the plateau, a world of extraordinary lunar scenery opens up, characterised by a dizzying maze of sandstone “forests”, stone deserts and labyrinthine canyons, monumental rock formations eroded by atmospheric agents, ravines and caves hidden among the stone backdrops carved by the numerous wadis that have now dried up. An incredible geological landscape that in turn hosts an extraordinary desert biodiversity, with the survival of some naturalistic species now extinct in the rest of the Sahara, such as the myrtle and the Saharan cypress.

But as the largest troglodyte site in the world, its uniqueness lies above all in the archaeological evidence of human settlements and civilisations that have followed one another over at least 10,000 years. With numerous lithic artefacts, mounds and concentric stone burials, and pottery from various periods, the Tassili N‘Ajjer contains the highest concentration, stratification and iconographic variety of rock art ever found, with some 15,000 paintings and engravings currently listed. An immense ‘Sistine Chapel’ in the heart of the Sahara, as it is commonly called.

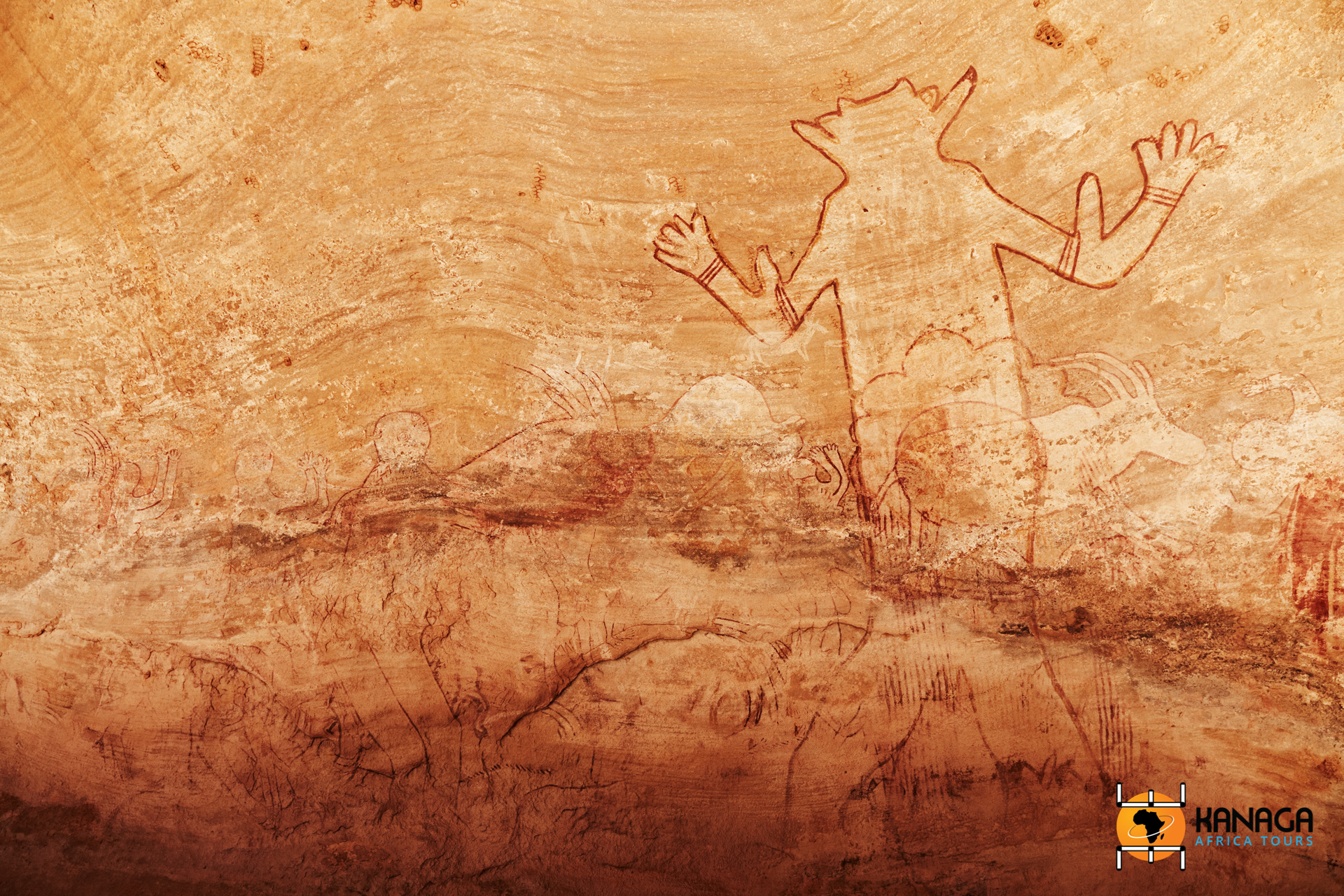

Henri Lhote, the archaeologist who made one of the first fundamental contributions to this immense heritage, wrote during his expedition in the 1950s: ‘actually what we have seen in the maze of rocks of Tassili is beyond imagination’. This phrase encapsulates all the astonishment one can feel when confronted with the most amazing examples of what is known as the ‘round-head period’. These are extraordinarily modern images, about which there are still many mysteries and unconfirmed hypotheses. Dating from between 6,000 and 8,000 years ago, they depict imposing anthropomorphic figures and animals with curious ‘Martian’ features. From the most abstruse conjectures that have hypothesised the presence of aliens on earth thousands of years ago, or of “hallucinogenic” shamanic rites in vogue at the time, today the most plausible hypothesis remains that linked to tribal representations of masks and vestments, in the context of ancestral rituals, or iconographies that refer to special burial techniques in the cult of the dead, with plant bandages and terracotta pots wrapped around the head of the deceased, thus giving the impression, for example, that the figures painted at Jabbaren may be reminiscent of astronauts or divers.

The sacred nature of these walls, caves and ravines, used as places of worship, is just as likely, as demonstrated by the impressive worshipping figures of the ‘God of Sefar’, with their deformed features, bizarre vestments and mysterious antennae on their heads. There are many hypotheses, but only one certainty: Picasso and Matisse knew where to draw their inspiration!

The Tassili N‘Ajjer is one of the most important open-air art galleries in the world, a reservoir of precious iconographies that tell the story of human evolution, flora and fauna, and the geology of the Sahara. They tell us about the time when the desert was a vast fertile region inhabited by wild animals such as giraffes, lions, buffalo with giant horns, rhinos, elephants and hippopotamuses, which are punctually portrayed in the most ancient graffiti and paintings; They inform us about the first organised societies, through ritual scenes and scenes of daily life, of breeding, hunting and agriculture; they offer us the first chronicles of war, of armed men on horseback and finally they confirm the inexorable and irreversible advance of the desert, in the depictions of the only animal able to withstand the aridity, the camel.

The Tassili tells us about all this, between imaginative iconographies, naive styles and incredibly realistic images, over a period of time spanning some 8,000 to 10,000 years, set against natural scenery of indescribable beauty and desolation, the Sahara.