© I. Fornasiero

Legend counts that when the powerful Malian empire threatened to wage war against the Senoufo people, who had always inhabited the savannah region in the north of present-day Côte d’Ivoire, they were confronted by an extremely peaceful people who were not interested in the conflict. The Senoufo, in fact, today as in the past, are mainly dedicated to agriculture and are admirable connoisseurs of art: weavers, dancers, sculptors, painters and skilled craftsmen, whose products are appreciated throughout the country.

The Senoufo symbols are among the most iconic and recognisable in all of West Africa and are replicated in all artistic manifestations.

Bicephalic masks with unmistakable features, tapered granaries, birds, antelopes and dancers are the main subjects that populate the famous Fakaha (or Korhogo) canvases, Ivorian cotton cloths hand-painted with traditional tools and natural colours, which even attracted the interest of Pablo Picasso, who is said to have drawn inspiration from them for the composition of some of his most famous works.

The same symbols appear on the dark wood of the masks and sculptures produced by the skilled carvers of the Koko district, in the centre of Korhogo, the capital of the region. The masks are made in the city, but it is in the sacred forest that they come to life, guarded and honoured by the initiated members of the secret society of the Poro ethnic group, which is the most important in the area and has the largest number of members. In order to avoid social stigma, all young Senoufo are required to complete an initiation course structured in several stages over a period of about seven years, during which the novices undergo various tests that enable them to understand and learn the secrets of the tradition.

For the Senoufo, leading a righteous life and pleasing their ancestors means following a series of dictates that have been codified over time, from birth until the end of their earthly existence, when an elaborate funeral ritual accompanies the deceased to reunite with their ancestral spirits. Only members of the Poro can take part in this ritual, which is of great importance in Senoufo culture, and they honour the deceased with a procession along the main routes of the villages, joined by large feathered masks, in the presence of which women and uninitiated people must avert their eyes in deference and reverence.

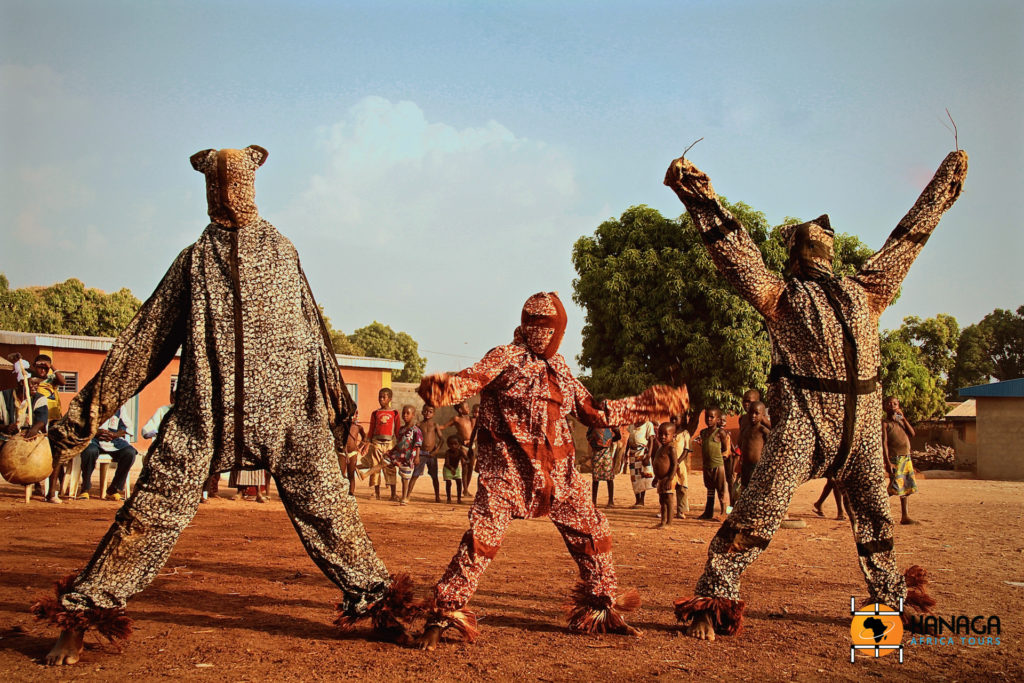

Originally conceived as a celebration dance for funerals, but nowadays also performed in more festive contexts while retaining its aura of sacredness, the Boloye dance, or the dance of the panther men, is an acrobatic performance performed by members of the Poro or by young people who are following the initiation path, which can also be witnessed as outside spectators. To the sound of drums and stringed instruments, dancers dressed in spotted suits that also cover their faces, perform a lively choreography that recalls feline movements and requires undeniable physical skills and bodies forged by long training.

While the Boloye remains a male dance, the Ngoron dance is reserved for the Senoufo girls. It is a choreographic performance in which the young women, bare-breasted, dance in a circle, accompanied by the songs of the village elders and the marked rhythms of the balafon and drums. Traditionally performed at the end of women’s initiation ceremonies, to celebrate the final transition from childhood to adulthood and the moment of the young women’s reintegration into the community, it is now also performed in honour of the most illustrious personalities visiting the village, as a festive moment of welcome and affirmation of social cohesion.

But the activities associated with the secret society of the Poro are not the only attractions of the savannah region.

Also in Korhogo, a short distance from the city centre, the sacred rocks of Sihenlow, large rounded boulders that are said to have descended from the sky, have become a votive place where people from all over the country come to seek solutions to their problems. Not far away, there are also centres for the production of ceramics and shea butter, run by women’s cooperatives, an iron forge in Koni and the village of Kapele, famous for the art of beadwork.

A few dozen kilometres further on, we finally reach Niofoin, a small agglomeration of huts and granaries, in the middle of which are majestic sacred houses with distinctive cone-shaped roofs. Centuries-old dwellings in which the village fetishes are preserved and to which only the initiated have the right of access.