© A. Pappone

In the heart of Mali, where the savannahs of the south meet the desert landscapes of the north, a fairy-tale world opens up, perched on the rocky ridges of the imposing Bandiagara cliff. The Pays Dogon, a magical place where the “people of the stars” have lived for centuries, with their ancestral secrets, based on one of the most complex cosmogonies of traditional Africa.

It is one of the most fascinating regions of the entire continent, rich in traditions, lunar natural landscapes, mysteries and magic, surprising clay architecture, of which the cliff is the fulcrum and treasure trove, an imposing 250 km long rock face, dotted with villages, the oldest of which were built on pre-existing Tellem settlements, in the 13th century, when the Dogon migrated from Mandé, settling in these inaccessible places to escape Islamisation and enemy invasions. Bandiagara is the capital of the Pays Dogon and the main centre of traditional medicine, based on the therapeutic properties of plants and divination, a branch that is so dear to the Dogon people and an integral part of their ancestral animism.

The first village we come to is Songho, famous for its traditional cotton weaving factories and the mysterious sacred circumcision cave, where initiation rites have been performed since the 13th century, with sacrificial offerings to ancestors and symbolic votive images (totems) painted on the rock face, which are renewed at each new circumcision. Heading north, crossing streams and lush terraced onion fields, we reach Sangha, the main village on the plateau, with its traditional dwellings, pointed granaries, the striking house of the hogon (village chief), enlivened by niches carved into the clay wall, or the sacred house dedicated to natural remedies, where fetishes, votive sculptures, potions of all kinds, animal and vegetable, or good luck charms (gris-gris) are crammed in.

At Bongo, an impressive and deep natural tunnel piercing a cliff face reminds us of the population’s past need to always have an escape route to use in case of enemy invasion. But looking at all the villages that line the ravines of the cliff, we can realise that the entire existence, first of the Tellem and then of the Dogon, was conceived according to a defensive organisation of the settlement and the communities, of which the granaries with the foodstuffs were the most precious thing to protect.

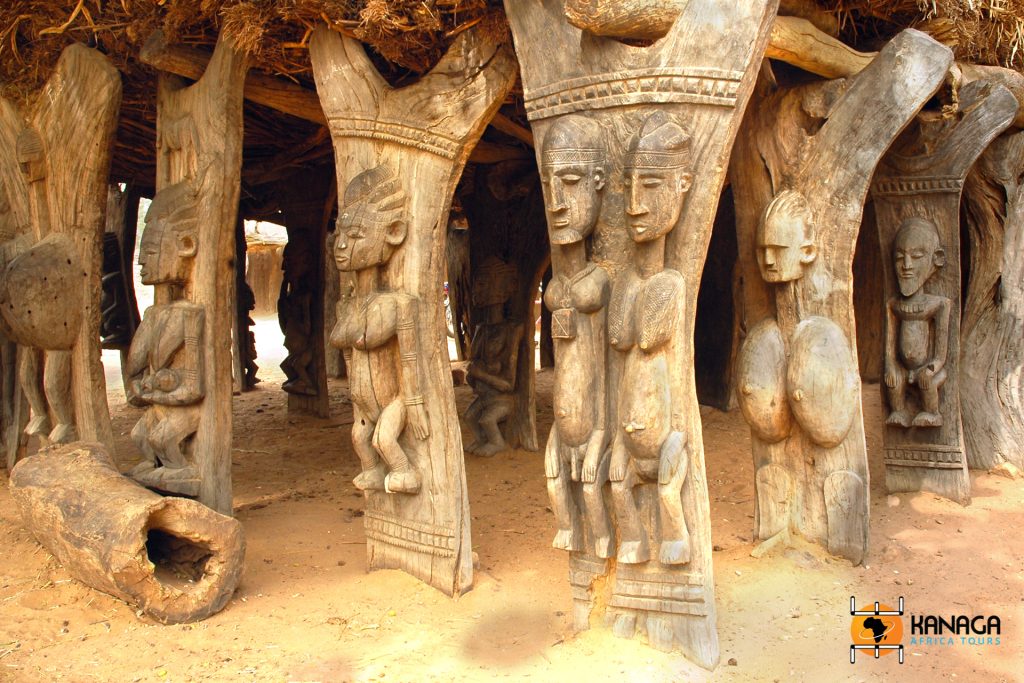

Banani, Gogoly, Ibi, Kundu and the marvellous three districts of Youga, dotted with ancient Tellem and Dogon granaries, hidden in the remotest cracks of the cliff, which can only be reached by a winding path of wooden ladders winding through the crevices of the rock. There are also Teli, Ireli (Unesco) and Tireli, where the clay granaries blend in perfectly with the rocky landscape, set in the most inaccessible cracks, accessible only by means of ropes lowered into the void from the top of the plateau, or by climbing the walls acrobatically from the plain. These are definitely the least accessible places in the Dogon Pays, and today they have been given a new sacredness that has transformed them from Tellem granaries into cemeteries of the Dogon ancestors. A few hours of trekking will take you to one of the most secluded and significant places on the cliff, reaching the village of Arou, where you will find the Hogon of all Hogons temple, the supreme traditional leader of all the Dogon people. Along the way you will meet the wise old men under the toguna, low canopies of inlaid wood and thatch, where important decisions are taken concerning the community, or the circular houses of the menses, where women avoid attracting the curse of family fetishes that despise blood.

Tireli is a village famous for its mask dance, around which revolves the essence of the Dogon’s complex cosmogonic symbolism, which is just as rich in the decorative motifs of the granaries and traditional dwellings, which display on their façades or on the carved wood of their doors and windows the theory of totem shapes and animals that are dear to the Dogon identity. The variety of masks is impressive and each one represents a symbol of principles universal to religion and animist beliefs. For example the Kanaga mask, whose meaning is to be found in the union of the sky and the earth, and in the rotating movement of the latter, demonstrating that, before Galileo, the Dogons already possessed advanced notions of astronomy and detailed information on the solar system.

Describing a population and a land so rich in ancestral customs, cultures and traditions stretching back thousands of years is a major challenge. Suffice it to say that around forty languages and dialects are spoken on the cliffs, or that there are rituals inaccessible to the uninitiated that have been perpetuated intact since the 13th century, some of them every sixty years. The best way to immerse oneself in the fascinating reality of the cliff and appreciate its complex cultural richness is to see with one’s own eyes the infinite facets that this land has to offer, to be savoured slowly by trekking on foot that allows one to capture the small daily gestures of the communities, approaching their spirituality on tiptoe, among sacred pools where caimans live undisturbed and fed, or old fetishists who predict the future, interpreting the jackals’ footprints in the sand, but also trying to understand some of the problems of a people who have made isolation the secret of their survival and identity.