Yorubaland, a term that geo-politically does not exist, but nevertheless identifies a vast African cultural region (including Lagos), in which a single people, the Yoruba, of about 40 million individuals, live in south-western Nigeria, but also in parts of Benin and Togo, united by the same language, the same history and origins, handing down from generation to generation, ancestral customs, traditions and spirituality, stronger and more identity-driven than progress and geopolitical separations, imposed by colonialism.

One only has to travel a few kilometres north and west of the megalopolis of Lagos to leave behind the chaos of the city and enter a world of ancient traditions, tropical oases imbued with spirituality and Orisha deities, guarantors of ancestral order and community identity, and the preservation of natural areas considered sacred, otherwise destined to disappear.

We are in the lands of the ancient Kingdom of Ifé, amidst coastal plains and tropical forests, mangrove tunnels and river estuaries, granite plateaus and rocky hills dotting the fertile valleys of the interior. Here developed the evolved agricultural civilisation of the Yoruba in the 10th century, governed politically by the leadership of the Oba chieftains, who are still active today, as well as by a colourful and mystical universe of voodoo deities, so characteristic that one speaks of a true Yoruba religion. Suffice it to think that many of the aspects of the spiritual manifestations of this people, are today recognised as intangible heritage of humanity by UNESCO, to realise how rich the Yoruba culture is, whose echoes reached and settled also in the Americas, through the forced deportations of the slave trade.

Badagry, Abekouta, Oyo, Osogbo, are still today important centres, repositories of history, culture and ancestral traditions, which developed over the centuries around the ancient city-state of Ifé, making a fortune with the production of palm oil, plantations of cocoa, gum arabic, cotton and yam, and above all with the slave trade. It was Badagry the main port on the Atlantic, which still retains the symbolic places of the sad memory of slavery. Obligatory stops in an introspective and touching visit to this historic place are the old slave market, a museum that collects the testimonies and objects linked to the sad trade, and the Gate of No Return, marking the exact point from which millions of individuals were embarked towards the Americas, under the protective gaze of Orisha Yemoja.

Among the Olympus of Yoruba divinities, the most evocative ancestral rites are those reserved for the Egungun, representing the spirits of deported ancestors, with their whirling movements and richly decorated costumes, those of the Epas linked to fertility, or the marvellous processions of Eyo dancers. A special place is reserved for the patron and benevolent goddess Osun, to whom Nigeria’s last primary forest at Osogbo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is dedicated. Here, every year in August, a collective ceremony is consecrated to her, amidst evocative prayers, sacrifices and voodoo rituals. The Osun Festival is one of the most sacred events for the Yoruba people, within the forest, where enchanted nature and numerous shrines and places of worship imbue the atmosphere with mystical devotion.

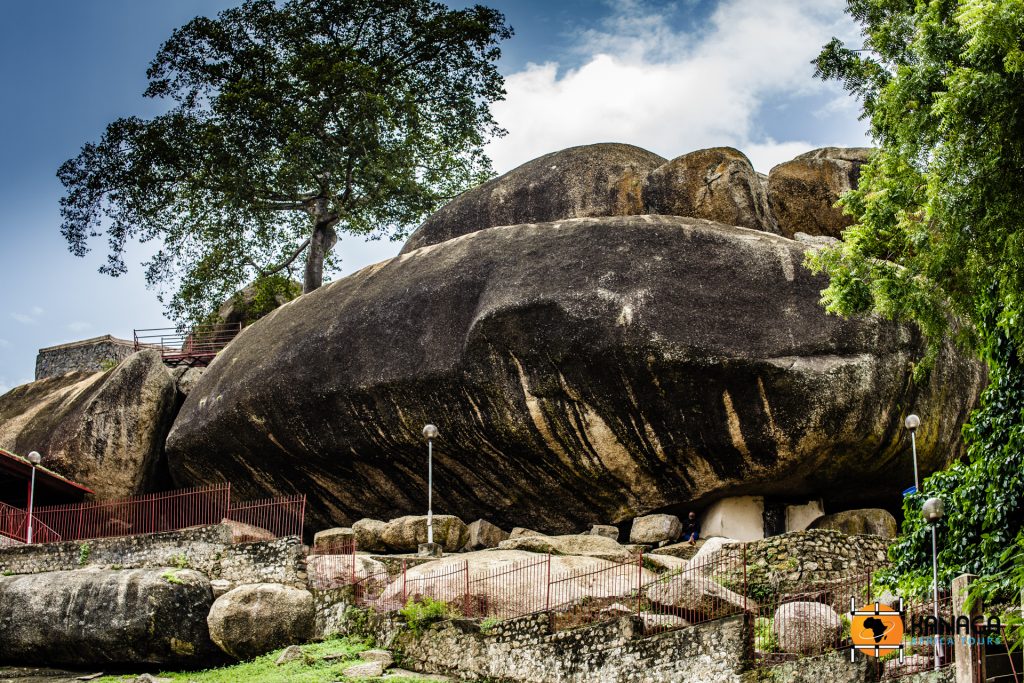

Also rich in history and mysticism is the city of Abekouta, founded in the 19th century by the Yoruba populations of the Egba subgroup, persecuted by the incursions of the Kingdom of Dahomey and those of neighbouring Ibadan, today one of the largest metropolises in Yorubaland. Surrounded by fertile lands and suggestive rocks from which it derives the very etymology of its name, Abekouta gathered around the impressive natural and defensive fortress of Olumo Rock, a splendid granite rock that dominates the city, still invested with sacredness, making it a destination for pilgrimages and ritual sacrifices. The magic in the once inhabited ravines of this place is also accentuated by the magnificent view of the city, the ancient clay walls, and the green cotton and oil palm plantations that surround the town.

Oyo, the capital of the ancient Yoruba Kingdom was instead the town of the same name, which was founded in the 19th century around the court of Alaafin, a title reserved for the local emperor who ruled from the ancestral royal palace, built according to traditional techniques and splendidly decorated with symbolic motifs. But the historical cradle of Yorubaland is undoubtedly Ifé, or rather Ilé-Ifé, whose foundation is lost in the mists of time and is linked to the very creation of humanity, according to the Yoruba religion. Although it was conquered by the Oba of Benin City and incorporated into the Edo Kingdom of Benin in the 15th century, Ifé remained the spiritual centre and most sacred place for the entire Yoruba people. Ancient shrines are still worshipped here today and are the destination of pilgrimages, amidst a colourful gotha of ancient Orisha deities, a rituality rich in ancestral traditions and accompanied by an artistic universe among the most precious in Yorubaland and Africa as a whole. A fantasy world of legends, myths and real history, the tangible remains of which reappeared with the first archaeological excavations during the 20th century, conducted by the German Frobenius. Objects of extreme refinement, in stone and terracotta, brass and copper. Anthropomorphic fetishes, animal sculptures and life-size busts, jewellery and masks, including the bronze mask of King Obalufon II, a 14th-century masterpiece preserved in the city museum. An impressive artistic sampler, modelled with extreme realism, and with a technical skill such as has never been seen before in archaic African art, making the Kingdom of Ifé one of the most evolved and refined in the history of the continent.