© L.F. Paoluzzi

Far from the beaten track in Tanzania and little visited, wrongly, by international tourism, is the surprising Maasai escarpment that opens up on the eastern side of the Rif valley in the Dodoma Region. A landscape of rocky hills enlivened by caves and ravines, in isolated and hidden places, where thousands of years ago the ancestors of the current Sandawe and Bantu populations took refuge, leaving behind a multitude of testimonies of rock art, among the most fascinating and mysterious in Africa.

Extraordinary sites in the area of Kondoa Irangi, near the villages of Fenga, Kolo, Pahi and Thawi, conceal, as if in a precious casket, a vast collection of rock paintings, scattered in about 160 recesses and ravines of the cliff, although probably many others are still waiting to be discovered.

Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2006, the hypotheses regarding their dating, which spans different eras, are discordant, generally suggesting a time span of around 2,000 years, or, according to some scholars up to 6,000 years for the oldest examples.

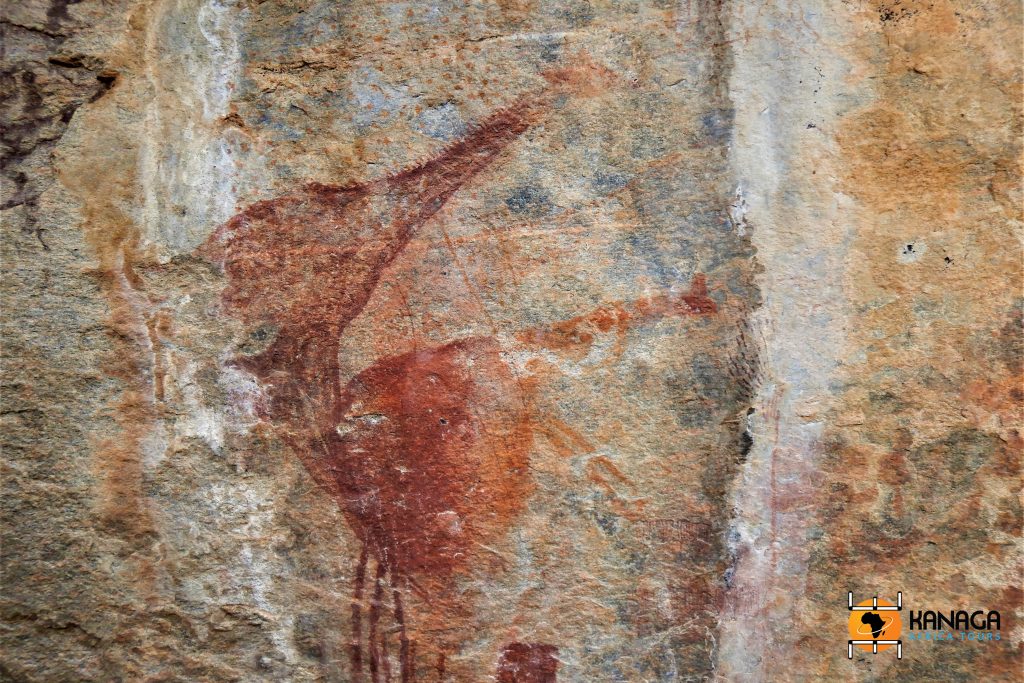

Among the most interesting iconographies are the marvellous elephant-hunting scenes at Fenga, or the ancient examples of stylised human figures with mysterious headgear or tribal masks at Kolo, which can be reached by 4WD and a mini-trek on the final stretch that climbs up the hill. But the largest and richest collection is undoubtedly that preserved among the isolated Thawi rock site.

An exceptional artistic and archaeological repertory, this immense collection of cave paintings is also a precious iconographic heritage on the anthropological evolution of the local populations, initially simple hunters and gatherers, and later organised into more complex and sedentary agro-pastoral societies. Some theories suggest that the most ancient examples were made by ancestors of the Sandawe, of San-Bushman family (an austral population with a long tradition of rock art), while the most recent ones are probably attributable to later populations of Bantu origin.

The images of wild animals, such as gazelles, elephants and giraffes, of domestic animals and stylised anthropomorphic figures, traced with red ochre, using a finger, are overlaid and layered with the most recent, fanciful symbolic dichromatic geometries, in black and white, with mysterious meanings.

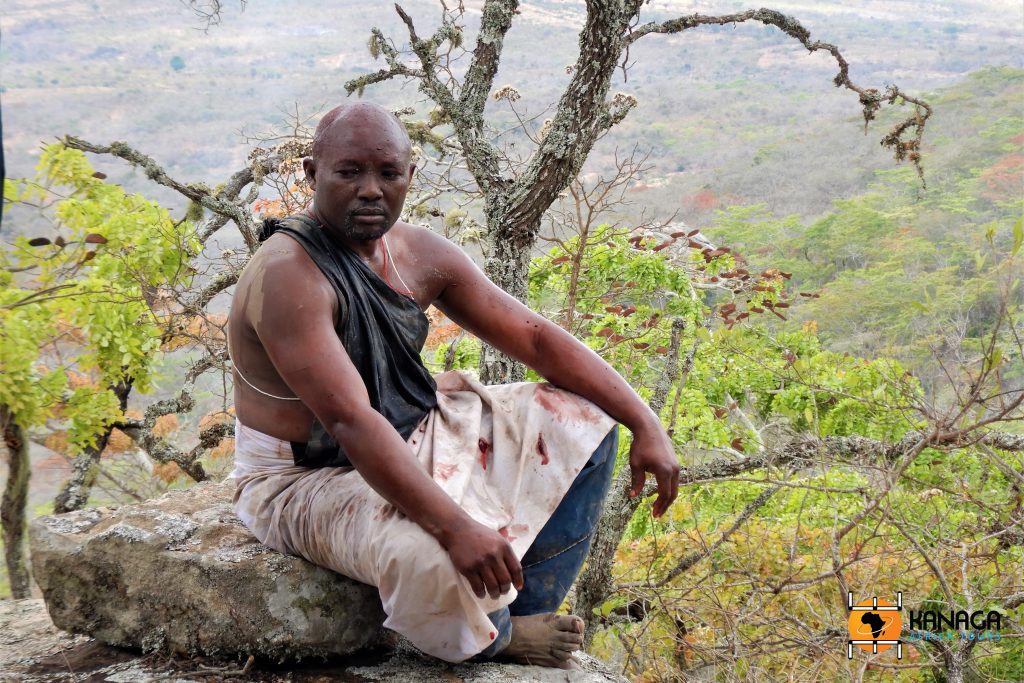

The uniqueness of these sites also lies in the fact that they are still used today by present-day populations to celebrate propitiatory rites and animist divinations, thus giving continuity to the sacredness of the places and the millenary culture of these peoples.

Beautifully preserved and some of them of the highest artistic value in their iconographic realism, the paintings are partly protected by the rocky recesses in which they are located, but mainly by the surrounding woodland vegetation, preventing the sun and erosion from damaging them.

An extraordinary place, a unique open-air natural museum, still virtually unknown and mysterious, which undoubtedly deserves to be studied in depth and visited at least once in a lifetime.